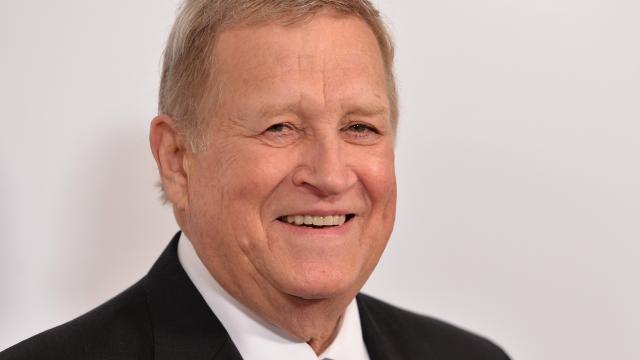

Whether he’s in a leading role or a supporting part, the writer or the director, JOHN LEGUIZAMO commands the screen, the stage, even the room. With decades-long success as an actor, writer, and producer, the Colombia-born, Queens-raised performer has taken on directing just once before (2003’s Undefeated). But he’s finally back in the director’s chair with the new inspirational drama CRITICAL THINKING. And with this new task, he had plenty of behind-the-camera inspiration to draw from.

As an actor, Leguizamo has worked with some of cinema’s undisputed visionaries, including Brian De Palma (Casualties of War, Carlito’s Way); Baz Luhrmann (Romeo + Juliet, Moulin Rouge!); Spike Lee (Summer of Sam, Miracle at St. Anna); George A. Romero (Land of the Dead); and Ridley Scott (The Counselor). He’s starred in blockbuster hits (the Ice Age and John Wick series), cult classics (Super Mario Bros., To Wong Foo…, Spawn), critically-acclaimed indies (Poison, Chef, Nancy), and TV juggernauts (ER, When They See Us). Beyond his on-screen acting roles, Leguizamo has had massive success writing and performing award-winning one-man shows on Broadway and off, including Mambo Mouth, Freak, and Latin History for Morons.

With Critical Thinking, Leguizamo takes on the dual role of director and star. Based on the true story of Miami Jackson High School’s champion chess team, Leguizamo surrounds himself with established performers Rachel Bay Jones and Michael K. Williams along with relative newcomers Corwin C. Tuggles, Jorge Lendeborg Jr., Angel Bismark Curiel, Will Hochman, and Jeffry Batista. Slated to premiere at SXSW 2020, Critical Thinking‘s rollout was shifted due to the coronavirus pandemic. Vertical Entertainment came on board as distributor and will release the film on VOD and digital platforms on September 4.

John Leguizamo was kind enough to take the time to chat with us about his newest directorial effort and the lessons he’s learned through his prolific career.

——

COLIN McCORMACK: With Critical Thinking, how did the project first come your way?

JOHN LEGUIZAMO: It was fascinating. I got offered to star in it by [producer] Carla Berkowitz, then they offered me to direct and I was like, “Yeah! I really feel like I can bring something to this movie.” Because I was a ghetto nerd myself. I understood what it was like to grow up in these tough neighborhoods and not have a safe space to be yourself, to be intellectual. That’s what these kids had. They grew up in Overtown, which back in the day was called Liberty City, which is really tough. Even when we were shooting, there was real shooting [laughs]. They tried to get us out of there at gunpoint. But I wanted to show that there was a really large smart, talented, intellectual group of kids in our black and brown neighborhoods that are just not being serviced, they’re not given opportunities, they’re not being funded. All it takes is one man or one woman who believes in them and gives them the time and the knowledge, and then all of a sudden you have superstars. United States national champions.

CM: Did you have any connection to chess in your personal life before coming across this story?

JL: Yeah, I played it quite a bit. I used to go to Washington Square Park where the best players used to go and I’d have my butt handed to me. But it was still fun, I always enjoyed it. Obviously, working on the movie I had to get a real fast upgrade. I had to learn at a rapid pace. I wouldn’t be able to tell you any moves now, but I had it all memorized at that time.

CM: Maybe I missed it in the end credits, but did you have a chess consultant or anybody like that on set?

JL: Oh, yes. All the real players who were in the game came and helped me and they helped the kids. I made sure the actors gave me a week before we started shooting and I rehearsed them. [We ran] lines, we improvised, we talked about character, the consultants were all there so the actors could meet the real people that they were playing, and they made sure we had all the real games. I wanted all the real moves. And they taught us how to play, how to throw the pawn or the king with the right kind of swag, and they made us look real, they made us look authentic.

CM: Yeah, I was curious about the chemistry between you and all the guys. In the indie film space, rehearsal is so rare – if ever a possibility – but it seemed like that connection was there with everybody busting each other’s balls.

JL: [Laughs] Yeah, yeah. Because you can’t manufacture that. It’s not even just indie film, most films they don’t rehearse and it’s a big loss. I come from theatre and I know how valuable rehearsal is and what you can learn. You create a team that way because you’re spending all this time, you’re rehearsing, you become real friends, that’s what naturally happens. I wanted them to feel – and I wanted to feel – close to them, and rehearsal gave us that. It gave us that confidence, it gave us the friendships that we needed because you can’t fake that on camera. You can’t. If you don’t bring it there, it’s not going to be there.

CM: Speaking of your theatre background, which connects to your writing background, what was it like for you as a writer to be directing someone else’s script?

JL: Dito Montiel, first of all, wrote one of the great scripts. He really knows how to write for young folk; he really brings those relationships out. And he’s a really collaborative human being. I was able to talk to him as I found and discovered more things about chess and chess class and teaching. He incorporated all that into the script. So it was a beautiful collaboration. I’d love to work with him on my next thing because he just delivers. And I challenged him every day, and boom, the next day there would be a new monologue, there would be a new scene. It was incredible and really collaborative.

CM: In terms of your past collaborations, when you were coming up as an actor, was there a specific film or on-set experience with a director that made you think, Hm yeah, maybe directing is for me also?

JL: Well you know, I’ve worked with some of the greatest directors and I think I’ve taken a little piece from everybody. That’s what I felt like when I was on the set, I was like, “Well, this is what Baz Luhrmann did when we were rehearsing;” “This is what Spike Lee did to create the camaraderie;” “This is what Brian de Palma does to create tension.” So I had all these great directors, sort of a catalog of these great techniques to use, and now I realize all these experiences I had really added up to something, really were worth something.

CM: You said they pitched you to direct. When you first read it, was that on your mind at all, or did the idea come from producers?

JL: I think somewhere in the back of my head, I was like, Damn, I would really like to direct this. You know, it wasn’t something I spoke out loud, but somewhere in the back of my brain, it was definitely fomenting.

CM: When I talk to actor-directors, I’m always curious about what the casting process is like for them being on the other side of it.

JL: Being an actor, it was much easier for me to go, This is talent. This is somebody who needs a little more work. This is somebody who I can work with. I knew who I wanted and I trusted actors more than I think another director would. When I see somebody’s ability, I care less about what they look like and more about what they can do. And I think that’s what actors bring to directing, that they care more about the ability than peoples’ looks or appearances, which is such a Hollywood thing. And I’ve been to a lot those casting calls where they’re looking for the way you look, the right height or the right build or the right face, and it’s like, that’s really the least interesting thing to me. To me, it’s about talent and ability. Can this person make me believe that they’re from this neighborhood and that they’re intellectual chess players? Can they give me that? Can they give me that they’re in a tough neighborhood but they can also be intellectual?

CM: You have such great young talent, it seems like you found some great up-and-comers.

JL: Oh yeah, dude. The thing was, there was a plethora of Latinx talent out there. And it breaks my heart because you know that this talent is being wasted and allowed to dissipate. There were so many great actors that it was hard to pick. I wish there were so many more Latinx movies and Latinx stories being told and directors including us in their storytelling. And I hope these things change soon because we’re the largest ethnic group in America with less than 4% of the faces in front of the camera and less than 3% behind the camera and less than 1% of our stories are being told. That’s a problem.

CM: And I think studies have shown, a huge swath of the movie-going population.

JL: Yeah, 25% of the United States box office is Latinx [ticket-buyers]. A quarter! And yet we’re not represented.

CM: In terms of your collaboration style and the people you’re working with, who did you come to rely on when you were in front of the camera?

JL: Definitely you gotta surround yourself with great people. I had the great DP Zach Zamboni, who was Anthony Bourdain’s DP for 12 years, so I knew he could deliver real and beautiful. Real behavior, documentary-style. I leaned on him a lot. I also had the incredible [producer] Scott Rosenfelt, who had my back and really helped me out when I had important decisions to make. And I had this great crew of actors, Michael Williams, Rachel Bay Jones; leaning on them was great because I’d go, “I’m confused about this scene, I’m having a little issue,” and then we would talk it out and they would help me make it better. I think art – especially filmmaking – is a collaborative process and the more collaborative you can be [the better]. I learned that from Baz Luhrmann and from Spike Lee.

CM: Was your crew comprised of local talent from Florida as well as people coming in from New York, LA, or other areas?

JL: Right, the crew was mostly all Miami-based. Zach might have been the only import. Then the actors, most of the main actors were all from [the area]. Angel Curiel is from Overtown, he grew up there. Jorge Lendeborg was from Miami as well. The kid [Jeffry Batista] playing Marcel Martinez, is from Miami down there.

CM: Working with Zach, I was curious of how you came to shoot the different chess scenes. It’s sort of like a sports film in a way, but it’s a sport where the players aren’t physically moving much. How did you figure out to shoot those in a compelling way?

JL: You cracked the code, bro. That was my message to Zack Zamboni. I was like, “I want to make this like a sports movie. I know chess is static, but I know we can.” And he said, “You’re right, we can.” And that’s how we orchestrated all those scenes, to make them feel like sports. A competition. And the last scene is like in a boxing ring in Rocky: Here are the two opponents under a ring of light about to duke it out ’til the end, you know? That’s how we conceived it.

CM: Was the [on-screen] ticking clock something from the script, or did you come up with that yourself?

JL: Well, there’s always a timer, but we used it to create tension. I had a great editor, Jamie [Kirkpatrick], who was a big help to me in designing, How do we create tension? I wanted it to be a tension-filled situation. I wanted it to be a battle, and the clock definitely helped us create a time lock, something to work against, an obstacle.

CM: Were there any particularly difficult scenes or sequences to shoot?

JL: I gotta say, that last [chess] sequence was really brutal. And thanks to the actors, because each one had 60 moves that they had to memorize. Then I had these great consultants. Marcel Martinez, the real kid who was in that scene – now a grown man – he was there and we studied that competition and all those moves. He would help us when the actors would forget – because it’s hard to memorize all those movies – he would yell them out and we’d have to reshoot it. We had all these extras, but it was a low-budget movie, and to keep all these extras and make this scene look huge and big like a national competition was really difficult with a low budget.

CM: So those moves were actually from the real-life match itself?

JL: Yes. All the scenes had the real, actual chess moves that were played by the real guys.

CM: I don’t know much about chess, but it’s nice to know that the angry chess people on the internet won’t come after you because you [recreated] it for real.

JL: Yeah, yeah! And my classroom scenes were like double-, triple-, quadruple-checked. I had the consultants there. “Is this right?” “Am I saying it correctly?” “Am I doing it right?” “How do I teach chess on film?” I wanted the audience to feel as smart as the players, so by the time they got to the last scene they thought they knew what the moves meant. [Laughs] Hopefully that’s what happens.

CM: Learning about the different methods and the history of it was completely new to me.

JL: That’s so cool, I’m glad you picked up on that.

CM: As an actor, what was your experience in the editing room? Some actors don’t even like to watch themselves, so I’m curious about how it is having to watch yourself over and over in multiple takes over the course of weeks?

JL: I don’t like looking at myself like when going to a premiere, where I can’t do anything about it. I don’t like that. But when I can do something about it, like looking at a monitor and then re-directing myself, I love that. Or in the editing room, when I’m deciding what to do with a scene, Do we cut this? Do we add this? I become sort of like another actor to me. But if I have to look at myself at a premiere, no, I hate that. Because there’s a narcissistic part of you, and then there’s a negative part of you as well, so you love and hate yourself. It’s brutal.

CM: The premiere at SXSW got canceled because of COVID, so your release strategy needed to be changed. How hands-on were you with figuring out a plan B to get the film out there?

JL: It was devastating. It was so exhilarating to know we’d gotten into SXSW, which is one of the best film festivals in America, and then not to have a real festival was heartbreaking. So there was one week of exultation and then heartbreak. Then we said we gotta move on. Luckily, Carla Berkowitz is a very collaborative producer and very hands-on and she’s very inclusive. She asked us all to participate – Scott Rosenfelt, myself, and [producer] Jason Mandl – and we figured it out quick: Let’s get on it, do a virtual bidding situation, create a virtual bidding war. And people responded. We had a lot of offers and we picked the one we thought was best for the movie.

CM: What’s next? As an actor, as a writer, as a director, what do you have going on?

JL: Well, I’m writing my comic book that’s being published by Image, by Todd MacFarlane, the great comic book creator. Image is like the third-largest comic book label after Marvel and DC. It’s called PhenomX and the Uncontrollables. All created by Latinx; illustrated, penned, written by. I hope people get a kick out of it and I hope it becomes a big franchise, that’s my dream with that. I’m writing a lot. I got a musical called Kiss My Aztec, which is like a Latinx Spamalot-meets-Book of Mormon and I hope that goes to Broadway soon. It’s gonna be hilarious, it’s so funny. It’s about the Conquest.

CM: That sounds awesome. You always seem to be keeping busy.

JL: Ya know, I’m an immigrant. I got the immigrant work mentality, which is work 24/7. I’m just grateful to be working [laughs].

__

Thanks so much to John for talking to us about his career and CRITICAL THINKING. Learn more by following the film on Facebook, Instagram, or Twitter.

If you’re an independent filmmaker or know of an independent film-related topic we should write about, email blogadmin@sagindie.org for consideration.