As a young actor, some of FRAN KRANZ’s earliest roles found him working for such esteemed directors as Antoine Fuqua, Ridley Scott, and M. Night Shyamalan. From his big-screen debut in the cult classic Donnie Darko to a lead role in The Cabin in the Woods, Kranz has acquired on-set experiences that would prove invaluable when it came time for him to make his own films. His first producing credit was on Casey Wilder Mott’s indie Shakespeare adaptation A Midsummer Night’s Dream (in which he also starred), but for his first film as a producer, writer, and director, Kranz stayed behind the camera in order to tell an intimate story about a still-too-relevant social issue.

MASS brings together two families in the aftermath of a high school shooting, where they meet to seek understanding and closure – and find out if such things are even possible. The film had a splashy unveiling at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival, thanks in large part to the thoughtful screenplay and stellar ensemble cast of Martha Plimpton, Jason Isaacs, Reed Birney, and Ann Dowd. It recently landed a Spirit Award nomination for Kranz’s writing and was announced as the Robert Altman Award recipient for the cast. Acquired by Bleecker Street Media following its Sundance premiere, Mass is now available On Demand.

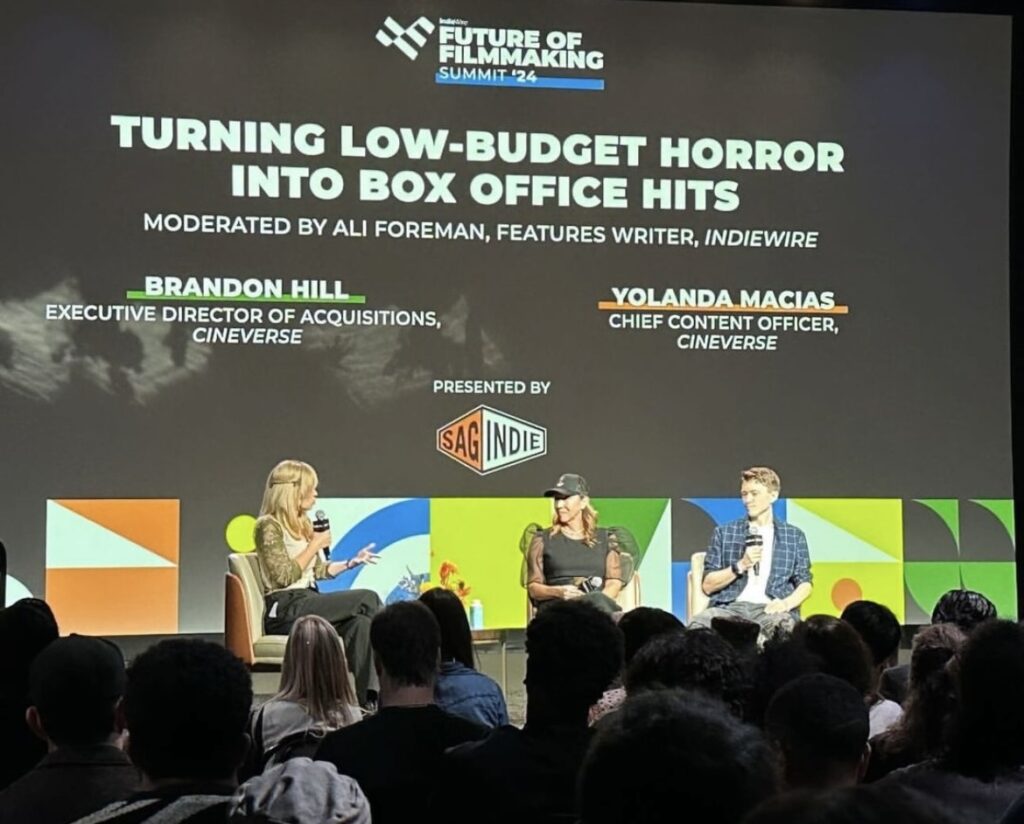

SAGindie spoke with actor/filmmaker Fran Kranz about his inspiration for the film, moving from acting to directing, and more.

——

COLIN McCORMACK: How early into your acting career did you start expressing an interest in writing and directing?

FRAN KRANZ: I always thought I was going to write and direct. As a young kid, I was making home movies and I would act in them, obviously. I just sort of assumed – I guess naively – that I was going to act professionally and write and direct professionally. The first one happened, but the latter two, I wasn’t coming up with anything. It was becoming a greater and greater source of frustration and anxiety and insecurity, thinking, Why haven’t I done something? Do I not have this in me? Am I afraid? What’s holding me back from taking that plunge and shooting something? I’m 40 now and I was about 37 when I wrote Mass. I had written scripts before, most of which I was too afraid to show people. I did have one script that I did show my representation, it was about aliens invading Earth. And they kind of thought I was crazy and didn’t know what to do with it. So I started lowering my sights and trying to come up with something I could do myself. Something I could finance myself and get my foot in the door, essentially.

CM: As an actor, were there ever expectations – internally or externally – to make a movie for yourself to star in?

FK: I’d definitely think about it; I have ideas in my head where I could play a part. It’s funny, as I get older I feel like I have a much more realistic sense of what I’m good at [laughs]. If you asked me in my twenties about starring in a movie I wanted to direct, I’d probably have more ideas, but nowadays, I know what I am as an actor. Also, once you direct, it’s very interesting to realize as an actor/director what you’re looking for. Someone can give a fantastic audition and it has nothing to do with what you’re looking for in the part. As an actor, so much of it is rejection that it was a valuable experience to be a director and realize it’s not always about the quality of your read. There are these intangibles that the director has in their head that will never have anything to do with your talent or how good of a tape you make. They’re just looking for a specific thing that’s sort of beyond your control. That’s actually given me a lot of solace as an actor. But I definitely have some ideas of things I could not necessarily star in, but be in.

CM: What inspired you to write this?

FK: I got the idea for this doing research about mass shootings in America where I learned about these meetings [between families of victims and shooters]. As soon as I read about these meetings, it reminded me of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa, which was a huge inspiration. A source of inspiration but also fear, because I did not know if I could partake in the idea of restorative justice. When I first learned about the TRC in South Africa, I thought, God, I would need retribution. I would need punishment. As much as I was inspired by it, it was also something that lingered inside of me with some uneasiness. Some 20 years later, when I came across these meetings – now as a parent – I thought that’s essentially what these people are doing: There’s this simple effort to heal by learning about the truth and possibly finding forgiveness and reconciliation.

CM: In that research process, going back to Columbine and sadly up to the present day, were there preconceived notions or elements from real stories that you wanted to embrace or shy away from when you were making a fictionalized version?

FK: Parkland was February 14, 2018. I had my first very rough draft by the end of April 2018, so it happened very quickly. I did about two years of research; I read nothing but books and articles and watched documentaries and whatever I could consume on that topic. At the same time, I had a script in about three months – or some rough form of it – and it was this meeting in a room. It was very specific. Once I learned that these meetings happen, I thought it takes such incredible courage and is such an admirable thing that I want to see more of in the world. I thought, That’s going to be the movie and we’re going to stay in the room. I had a very strong conviction about all of that. But my research hadn’t gotten very far in three months; I couldn’t tell you how much I had read up to that point. The conversation and, specifically, my fictitious version of the event itself evolved over the next year-and-a-half or two of the writing process. It sounds insensitive, but I refer to it as a Frankenstein’s monster of a [mass] shooting.

As an actor, I was essentially improvising in my writing process, playing the father of the victim, the mother of the victim, the father of the shooter, and the mother of the shooter. I tried to open myself up to those perspectives as much as I could and whatever resonated with me in any of those four identities in my research I put into the writing. I would connect with something – whether that be a detail about one of these tragedies or a personal detail about their home life – and I would write about it and improvise dialogue around this piece of information. Then obviously, there was a long, long editing process and this is what evolved. It’s all very sadly based on reality. This movie is fiction, but the events that inspired it are not and I never felt I was stepping outside of that while writing it.

CM: You mentioned earlier about having hesitation in the past about sending your writing out. What did you do with this once you finished the first “presentable” draft?

FK: It’s funny, this one was so serious. I told you I [wrote] an alien movie and I think it’s a really cool alien movie personally [laughs]. I still like that script, but maybe there’s some level of sheepishness or embarrassment about, “Here’s my big $100 million blockbuster, what do you think?” It’s like, Who are you? What am I supposed to do with this? That was essentially the reaction. Whereas with [Mass], I’m crying in front of my laptop for a year-and-a-half. There was a heaviness and a seriousness of purpose to the whole process that was unlike anything in my life. I can only associate that with the fact that I was a new parent at the time of writing it. I was very much overwhelmed with new feelings and new anxieties of being a parent and so I had a lot of humility with the script. So I asked for a lot of notes and a lot of opinions. I sent it to a lot of people and in many ways, I didn’t really know what I had because it was such an emotional process. It’s sort of strange that since it was so emotional, maybe it would be harder to show, but at the risk of sounding pretentious, I felt a real responsibility to share it with people. I felt a real urgency to finally make this one. This was the one. It’s in a room and it’s one location and this is finally the thing I can feasibly do. I know I can do this and I can afford this and find the money to put it together and I know great actors. This one felt so within reach that there was a real urgency on my behalf to share it and know what I had. For the most part, the response was all very positive.

It was good to begin in a collaborative mindset, because ultimately when we got into the rehearsal with the four actors – Martha, Jason, Ann, and Reed – I was still in that mode of collaboration. That mode of, You tell me what this is. You tell me what you think. You tell me what’s wrong or what you want to see. That was essential to our rehearsal process that they had all the beats that they needed to get to the emotional place they needed to go and that there was no confusion or apprehension or dislike of any line they had. I needed them so locked in to carry them on their way, so to speak. It might be different with other scripts – if it’s genre or period – or maybe there are certain times where a script shouldn’t be so open and flexible. But with this particular story, in that it’s essentially one long conversation, it was really important to me at all times to hear where people felt it wasn’t natural or they did not believe a character would say this, or this might be information these people already have. Sometimes I felt – because, again, I’m sitting there crying in front of a laptop – it was important to have four objective perspectives.

CM: Speaking of that cast and collaborators, what was the process for casting those actors? Did you have any previous relationships with any of them or was it through a traditional casting process?

FK: Reed and I became friends through doing theatre in New York. We had mutual friends and I was such a fan of his. I would go watch Reed Birney plays at Lincoln Center on the Theatre on Film Archives, I was such a crazy fan of his. I think he’s truly one of our great living stage actors. I wanted stage actors for the movie because I felt we were going to have such long takes and coverage that inevitably shows all four of them. Reaction is so key to this movie and being engaged at all times that there are no opportunities to take a backseat when the coverage is on someone else. We would have two cameras, we would shoot in such a quick and efficient way that you just wanted to trust that all four actors were completely present and reacting in real-time. I associate that with great theatre actors.

I had Reed in mind from the beginning; I wrote the part for Reed. I think he got sent a draft in October 2018. Then the others kind of fell into place. I had written thinking about some actors from the New York theatre community. By the time we went to go shoot, it became a question of who’s available and who wants to make this movie for no money [laughs]. It was a very different story. The thing that really was a game-changer was getting a casting director; Henry Russell Bergstein and Allison Estrin. Before that, I was just a guy with a screenplay. I was an actor cold-calling agents with a screenplay and no one wants anything to do with you. To get quality casting directors as representatives of the film was huge. Almost overnight, the perception of the project changed. Then obviously, having a date and a location makes it very real, very concrete. Once that was in place, you started seeing lists of names. I heard Jason Isaacs wanted to meet and then Martha Plimpton wanted to meet. The whole thing became beyond my wildest dreams in terms of the talent that was assembled. That speaks to the supporting actors as well; they’re incredible in the movie and what they do is so much more important than I think some people realize, how they set up the tension and the premise in those first 15 minutes.

CM: From filmmakers I’ve talked to, it seems like rehearsal is pretty rare on a low-budget film. Sounds like you were able to bring your actors together to rehearse? Given their theatre backgrounds, I’m sure it was appreciated.

FK: Yeah. It was relayed to me, politely, from Martha Plimpton’s representation that she would probably not do the movie unless there was rehearsal. Luckily, I felt the same way. I felt we can’t do this without a rehearsal. We can’t just show up in Idaho. It was a 14-day shoot and as soon as the door closes on the four parents and they’re left alone, it was an eight-day shoot. It was the last eight days of the shoot, so nothing could go wrong. We’re doing 10- to 12-page days the first five, then slowing down as things became more emotional. Martha had worked with Sidney Lumet on Running on Empty and they’d had a very intense rehearsal process, so by the time they got to set, they knew exactly what they were doing and it loosened them up in a way. That’s the way theatre works. It was clear in my mind we needed to do that, but it was also emboldening and inspiring to hear Martha Plimpton say, “I did this with Sidney Lumet.” [Laughs] That was very cool and exciting to know that’s what she wanted with that incredible film with a great director. I thought, Yes, we’re going to do this. We’ll move heaven and earth to make sure we find the time.

We ended up with two-and-a-half [rehearsal] days, which I think changed the goal and the intention of the rehearsal process a little bit. It became a crash course in dissecting the script. We never ran through the scene in one sitting. We never read through it, but we picked it apart and asked questions, and did what you call table work. We would read and if someone had a thought or observation or question we would stop and work through it and we changed the script in real-time as we felt we needed to. I really, really tried to give the actors freedom and authority to speak their minds. Again, I knew they needed the beats in place to get to these emotional places. You have Martha Plimpton for an entire day giving this very cathartic, very emotional speech and she did it all day long from every angle. It felt sort of superhuman, but I do think it was a testament to allowing her to [ask], “Can I say this?” Or, “I don’t know if I would say this.” Or, “Maybe there’s some other concept here that is hurting this woman. Can you and I together excavate that and find new text to speak to this emotional beat?” This is how it worked. I use this example of Jason Issacs all the time, but we had a scene where Richard and Linda – Reed Birney and Ann Dowd – are talking about the day of the shooting from their perspective, one speech after another. Reed talks then Ann talks then Reed talks then Ann talks, and Jason just cut in and said, “I don’t want to listen to this. Why am I listening to this? I don’t care about their story.” And it was such an honest response that we essentially wrote it into the script. In two-and-a-half days you can only do so much, so it was important to be open and collaborative.

CM: Because it seems like it was such a well-oiled machine, in terms of the script being so precise and the conversation so structured, is it presumptuous of me to assume that would transfer to a smoother post-production process? Was shaping it in the edit still full of twists and turns you didn’t see coming?

FK: I’m not going to be good at answering this question because I’ve never edited before and I had never been in post-production as an actor. I had a total panic attack. We finished right before Thanksgiving. December, I started handing over footage. I started looking at footage myself and I started to realize very quickly that I’m never going to find the movie [laughs], and had a total panic attack. Now I realize it’s a process that just takes time and you need to sit with the footage and watch and watch over and over again. It’s a hard process, but initially I completely panicked. I was very naive as an actor. I thought the wrap party was it. I was very emotional at the wrap party as if I’d accomplished something, but you basically haven’t really accomplished anything yet.

I will tell you this, the aesthetic was mind-numbing, being in that same room for 75 minutes. Our camera movement tried to mirror or parallel the emotional arc of the characters, but you’re still in that room, which is essentially very neutral, nearly white walls. There’s not a lot of change so you kind of lose your mind a little bit, but we were creative that way as well. A lot of times we were pulling reactions and even sound from different parts of the conversation to construct the scene you see in the movie. If we felt, “I could really use an exhale right here from so-and-so, but we don’t have it.” “Let’s find it from some other scene.” It was nice in that sense that there was a bottomless well of options. But that’s what made it so overwhelming to begin with. I really remember thinking, I’ll never find the best version of this movie. And then we had a rough-cut screening on February 24, 2020, right before the pandemic, and I was so nervous it was going to be the most boring movie ever. It was not a problem, it went very, very well.

CM: It’s nice to hear you at least got to see it with some people before things locked down.

FK: 100%. I don’t know what would have happened with this movie without that screening because it was validating. Like I said, I was really nervous. I really was concerned it would be the most boring movie ever with four people at a table, but it was the least of our problems. We had these key areas – the beginning and the end – and certain big decisions we tried to make with the camera and an aspect ratio change and cutaways. Those were the parts of the film that needed further conversation between our creative team. But the four actors in the room at that table? It just worked. If I didn’t have the opportunity to see people in a dark theater crying at the end of this movie, I don’t know what sort of choices I would have made going into the pandemic out of insecurity or uncertainty or lack of confidence. From the very beginning, there was concern that you couldn’t pull this off, this conversation. Is it going to be compelling enough to sit through? Is this movie going to work as a movie? Had we not had that screening, I just don’t know if I could say with any certainty that the movie works.

CM: Now that the film is out for all to see, what’s next for you, in front of or behind the camera?

FK: I did season one of a show about Julia Child called Julia that will be on HBO Max I think in March or April. It’s fantastic. Sarah Lancashire plays Julia Child, David Hyde Pierce plays Paul Child, Bebe Neuwirth is in it, and Isabella Rossellini. It’s an amazing group of people and a really fun, bright, charming show. And it was very exciting to just be an actor after doing the directing thing.

But Mass has been a full-time job. I wrote and directed but I also produced, I also was a financier. I am still so busy with Mass, trying to get it out there, still dealing with distribution and foreign territories. We just came out on Video On Demand and I’m hoping we can have as far a reach as possible now because of that. I wake up and I feel like I’m still working on this film the same way I did at five in the morning when I was shooting in Idaho. It’s the same kind of get-up-and-go belief and determination to get this movie in front of people. It’s wonderful and it’s been one of the most rewarding journeys of my life. It’s also a little scary because I don’t know how to move on and I don’t know what that’s going to look like or when that’s going to happen [laughs]. But I have some other ideas for movies and I’m writing something I’m excited about. I’m afraid I won’t be a director who turns out movies every couple of years. I think it’s going to take me a little more time.

__

Thanks again to Fran Kranz for talking to us about MASS. Learn more about the film at mass.movie or on Instagram, Twitter, or Facebook.

This interview has been edited for clarity.

If you’re an independent filmmaker or know of an independent film-related topic we should write about, email blogadmin@sagindie.org for consideration.