As a child who came of age in the late 70’s and early 80’s, I first became aware of ROBERT ALTMAN indirectly, through the television version of his breakout film M*A*S*H*. The self-serious, laugh-track free show (which by then had been completely and tragically Alda-ized) gave no indication to me of the anarchic, subversive humor of the original film – and anyway, at that point in my life I was much more interested in the exploits of the A-Team or the Duke boys. Mopey doctors making soulful eyes at the camera was not what I was looking for in my television entertainment.

As a child who came of age in the late 70’s and early 80’s, I first became aware of ROBERT ALTMAN indirectly, through the television version of his breakout film M*A*S*H*. The self-serious, laugh-track free show (which by then had been completely and tragically Alda-ized) gave no indication to me of the anarchic, subversive humor of the original film – and anyway, at that point in my life I was much more interested in the exploits of the A-Team or the Duke boys. Mopey doctors making soulful eyes at the camera was not what I was looking for in my television entertainment.

In 1980, I saw my first Altman film, in a theater in Dothan, Alabama: it was Popeye, an ill-conceived excursion into the musical genre which, though starring one of my favorite ugly-hot actresses, committed the ultimate sin in the eyes of a 12 year old boy looking for a good summer movie – it was boring. It never came close to capturing the kinetic energy of the Popeye shorts, and the maudlin songs and lifeless production design were surefire snooze inducers.

Even though I saw The Player (which wannabe filmmaker didn’t see it?), it wasn’t until film school that I began to appreciate Altman, and it wasn’t even M*A*S*H* (as good as that movie is) that sold me. Instead it was the dreary adventures of one John McCabe, wandering through a rainy, cold frontier town in McCabe and Mrs. Miller, that drew me in. The overlapping improvised dialogue, the flat planes of his compositions (an element of his style forged during his early career in television), the pans which followed the characters in head to toe shots through their environment – his idiosyncrasies all came together for me in that film, and for the first time I got it.

It was those idiosyncrasies which marked his work. Sometimes they worked for him (The Long Goodbye, Nashville) and sometimes they produced train wrecks (Pret-a-Porter, Brewster McCloud), but he stayed true to his vision, and after a long, post-Short Cuts, stream of critical and commercial failures – including the overlooked and underrated Cookie’s Fortune – that vision was vindicated (in yet another of his many comeback films) by the success of Gosford Park.

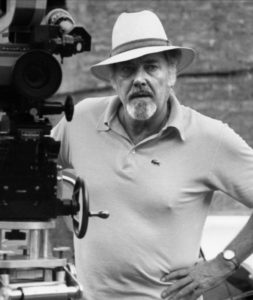

When Robert Altman died yesterday, he left an incredibly varied body of envelope-pushing work, including at least three undisputed classics. He was hugely influential amongst independent filmmakers. He worked as a director for 55 years, and he worked right up to the end. He had an admirable persistence of vision. He did it the way he wanted to do it and, in the end, who can argue that he was not right?